Tiktok and Living Labour

Tiktok has been the social media of choice for working-class self-expression in recent times.

Capitalism comes to town with the promise of ‘choice’, while establishing its hegemony. Democratization in terms of user/consumer choice/voice is rolled out – with a deeper penetration of the logic of capital. Many nowhere people and nowhere lands (and zones of ‘imploitation’) are brought into it’s ambit – who then also attempt to take matters into their own hands, and realize the limits of the system. The rise of social media is part of this process. It is an advance from print and mainstream media, where the control by dominant class-caste power structures is more direct.

Photo by Rahul M

Tiktok in the past 2-3 years has also been part of this process. It additionally removed the mediation of the written word, of editorial or expert hierarchies, and jumped over this ‘translation’ into unfiltered expression through/of the body. Its 200milion user base with 119m monthly users in India has been markedly different from the Facebook, Twitter, Instagram public sphere. It has been thus – not only in its diversity and talent from the rurals and moffusils – but in the framing of life, work, leisure and time itself. The proletarian being rears to emerge beyond ascribed role of a commodity, the proletarian public sphere seeks formation

Democratization and the Unpretentious body

Because of its format of the 15 sec video, anyone or their friends with a smart phone and internet connection could upload a quick take. Tiktok thus managed to reach the country’s rural areas, small towns and urban ghettos. Diversity of talent, and Eklavyas, of course abound in the country. Daily wage workers like Arman Rathod became ‘Tiktok stars’, the selfie stick and the bullock cart leash coalesced.

The recent Youtube vs Tiktok via Carry Minati vs Amir Sidiqqui debate found itself being framed as Indian nationalist, middle class sophistication, Hindu vs working class crudeness, anti-national, Muslim, and so on. Many of the top Tiktok ‘influencers’ were Muslim and young women with upward social mobility ambitions. This didn’t go too well with the ‘proper’ middle classes, and the hyper masculine Hindutva nationalist status quo – whose IT cells could not fully control its algorithm either. Not that the SGPC or the Shahi Imam liked it, banning it from religious worship premises, they outline how to identify a Tiktoker, “one person makes the video and the other enters the frame either dancing or jumping or doing some such thing. This is when we know it’s a Tik-Tok video.”

A recent ‘Goodbye Tiktok’ video by AIB’s Tanmay Bhat said, “things like feminism, women’s rights haven’t yet reached Tiktok”. Well, spaces where one thinks it has reached often opens into a house of horrors.

Against it, there are voices of women themselves on Tiktok who assert a completely different story. A housewife replying to a comment on her video, says,

“we were earlier stuck in the morass of housework and children and their che-che pe-pe, but in the last few years, the mobile phone and then Tiktok arrived, and now masti chadd rahi hain, chadhne do (we are rolling in fun, let us roll)”.

She advises the other woman, Laali, to “not halt the masti.”

No halo of reproductive work here. Linked to production, even this sphere is cursed as long as we are slaves of the productivity logic under capitalism and patriarchy. Another video by a young girl while scrubbing utensils, comments on marriage,

“Why do girls cry so much as she leaves her parental home on marriage?”

Pat comes the reply,

“If someone takes you far away from home to scrub dishes, will you dance to it?”

Users among working class dalits in the margins of the urban found one more way of asserting their being and dignity. Beyond casteist division of labour and victim-hood representations, what found self-expression was skill, strength and joyous irreverence.

The peripheries already speaking for themselves, also would point to the sham of the bridges to the mainstream, of promises of ‘development’ during elections, and refusal to take these promises or doles any longer, and so on.

Unmediated by experts, collaborations and digital social-solidarities previously unthinkable abound, between working class boys from south India with Korean Tiktokers, women coordinating dance moves, of lovers showing each other their living quarters and life-worlds to an old romantic tune or even critiquing heteronormative world views.

Civil Society vs Political Society, a recent history

Such rapid spread of forms of expression bring with it the representative majority – with their aspirations, frustrations, emancipatory impulses borne of unbearable situations, and crude forms. They come to the gates of the real limits of the system, wondering about their own role in its reproduction and transformation.

The Indian State has been consistent in invisibilizing labour, in its apathy. It facilitated both communalization of the virus and marking labour with casteist contamination fears. It is hand wringing on the question of public health. It willfully loosened it’s own intervention capacity in regulating the economy (the ‘Aatmanirbhar Reforms Package’) and in mediating labour-capital relation (pro-corporate changes in Labour Laws) as neoliberalism demanded. At the same time, upscaling it’s security, surveillance, repressive apparatuses. Using draconian laws, it is arresting and hounding hundreds of anti-CAA protestors, with the pandemic as opportunity. Each of these moves had hundreds of Tiktok video commentaries.

The State’s actions were nothing new per se. What was new is that during the Lockdown, a major section of the working class, the migrant workers, suddenly made themselves socially ‘visible’. They did so by collectively finding themselves in the dispossessed situation that they did in such numbers, and undertaking epic journeys across the nation. When ‘work-from-home’ was supposed to be implemented ‘for all citizens’ – reaching home itself became the major point of self mobilization for the wage hunters and gatherers. By this act of the collective body itself, it asserted its existence and political right of being – showing that majority of this class has never reached substantive citizenship. Tiktoking workers questioned ‘is the worker a citizen?’ Thus they plotted continuity in the anti-CAA and Covid phases.

The breaking down of the fiction of socio-political equal citizenship and loosening of its control, made the State very uncomfortable. It acted with its usual repressions, but it was also unsure and forced to undertake some retreat. Around 160 or so migrant worker lockdown-related class riots with the police were recorded (see ‘migrant worker resistance map’).

Unruly forms, imposed as a reaction to increasing stringent systemic discipline and surveillance. Along with whatsapp forwards, Tiktok was again abuzz with these impulses. Few expressed submission to fate, but most its obverse, the messiness and clarity of rage. In Tiktok, one saw immediate reporting of its fallout like food riots. A video uploaded on Tiktok called ‘loot in a station’ said to be of Jabalpur station, got around 20million views within a day, before it got taken down, but not before various re-dos sprang up and circulated. The majority of comments in such videos were revealing of the working of the popular mood in its unprecedented support, even while contextualizing and being self-reflexive about the actions forced upon workers by the situation.

In majority of even the positive reporting and analysis in print and mainstream media however, this basic lesson was overturned: workers were portrayed as perpetual victims seeking help of others, and not as active makers of society. If you see the workers own self-representation however, it had its share of real pain but also had irony and irreverence, even mazak. While waiting for a lift walking thousands of kilometers, there were videos of dancing and reflecting on the absurdity of wage work. In their own style. Is there one such reporting or analysis one remembers of workers in this period?

On managing to return home, this worker puts up another Tiktok video continuing the theme of reflection, “zindagi mein pehli baar esa ho raha, ki main din-raat so rha and koi kuch nahi bol raha (first time in my life, I’m sleeping day and night, and no one is saying anything).” Self-depreciating humour was never late in coming. A video showing thousands of workers stranded on the streets quips, “haaan, now (with the lockdown) we know that so many mazdoor stay in Delhi and Mumbai, otherwise back in their villages, everyone would call themselves as ‘supervisors’!”- wider unity of the class visible, beyond internal segmentation.

Many Tiktok videos of journeys back home had background music of the popular sandeshe atein hain song from the film Border, self-comparisons of migrant workers with soldiers, rewriting Indian nationalism so to say. Everyone had their truck hitchhiking Tiktok video.

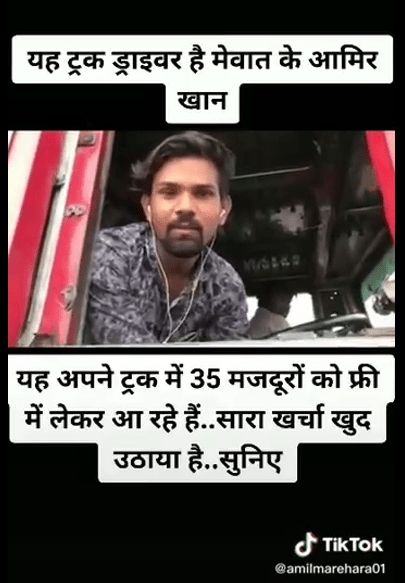

Hundreds of videos on real solidarities found self-expression without relief-as-camerawork. Self-organized solidarity by the oppressed, providing relief as the state withdrew, truck drivers giving free lifts while handling corrupt police officials, and so on.

Some journeys took deeper human root, friendships and love marriage while walking back home, duly reflected with their Tiktok videos. Even the quarantine time-pass and music was distinct from the boredom and abstract nostalgia produced by the middle classes.

From Corona to Amphan to the State’s handling of the conflict with China, Tiktok again was abuzz. A video asks, “Had to ask the government something: the electricity meters in our homes are made in China, so should we uproot and throw them away? Anyway, the electricity bills are coming quite high!”

Self beyond the commodity: Living labour vs dead labour

Consciousness can never be anything else than conscious existence, and the existence of (wo)men is their actual life-process

Karl Marx, German Ideology

More than the exceptional situations of protests and Covid however – it is the normalcy of exploitative relations in which the formation and expression of the working class require appreciation. Labour as wage-work is boring, repetitive action under conditions wherein living labour is subsumed into dead labour or capital, the ‘growing organic composition of capital’. “Capital is dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks,” said Marx, and against it, “If the labourer consumes his disposable time for himself, he robs the capitalist”.

Living labour oscillates between submission and revolt – but the indeterminate, recalcitrant human freedom from within labour that allows for the generation of value, cannot let itself be completely subsumed by dead labour. As capital deploys more capillary mechanisms of control and discipline, labour meets every process of violent expropriation with an act of intransigent willfulness. It revolts by collective organized action, but also daily through individual and collaborative subversions, go-slows, time-pass, daydreaming, re-finding skill and militating against alienated labour, and challenging the clocks and ‘targets’.

It is here that mediums like Tiktok found relevance as escaping drudgery. This is of course through a medium which itself operates under rules of capitalist profit. Even so, it contradictorily provides an avenue for workers to move beyond being passive consumers of entertainment as with other media, and themselves acting out the escape from subsumption in real time. More than about the reigning ideas of politically correct or incorrect nature of the content, the ‘time pass’ during break-time and reproductive time, and imagining a way out of control within the ever-expanding productive time take precedence.

A proletarian public sphere?

The invisibilization of labour has a systemic consensus. It is to be kept outside the theatre of society and politics. Its corollaries include a casteist derision of dignity of labour. Repression and humiliation is labour’s lot to keep this internal logic of exploitation or capital at play. As labour militates against it, it asserts its living collective body and the ‘actual uncertainty of life’. Of these unrealized working class interests, the ‘proletarian public sphere’ of political society seeks to form. As such, it is not yet realized and exists in a fractured oppositional manner – distinct from the public sphere of civil society with its norms, limits, separation of powers.

In Tiktok, as talked about earlier, lip sync, mimic and inspiration videos aping Bollywood abound. But this reproduction of the popular mainstream art and cinema (which itself, since the 90s neoliberal phase, has largely forsaken representation of working class life-worlds) is not merely passive. They have their own voices, moves and twist to the stories, with real ‘settings’. Both the art and its expression are not ‘formed’, in the ways in which traditional art is coherent, systematic and sanitized. It has unsophisticated jabs, self-depreciating fun, questions to the system, and new disruptive solidarities.

Thanks to Johana for many of the videos and Jiten Bezboruah for some of the insights

Be First to Comment