There has been a lot of talk about what exactly ‘Azadi’ (freedom) means, especially in the wake of Kanhaiya Kumar’s post release midnight speech at JNU on the 4th of March. So lets talk some more. No harm talking. If there is noise, there must also be a signal, somewhere.

Kanhaiya Kumar clarified in his electrifying, riveting speech that his evocation of Azadi was a call for freedom ‘in’ India, not a demand, or even an endorsement of a demand for freedom ‘from’ India.

This may come as a sigh of relief to some, – Kanhiya , the man of the moment, proves his ‘good’ patriotic credentials, leading to an airing of the by now familiar ‘good nationalist vs. bad nationalist’ trope. And everyone on television loves a nationalist, some love a good nationalist even more.

Perhaps this was a way of dealing with a bail order that was at the same time a gag order. But to say just that would be ungenerous, and miserly, especially in response to the palpably real passion that someone like Kanhaiya has for a better world, and for a better future for the country he lives and believes in. I have no doubt about the fact that coming as he does from the most moderate section of the Indian Left (the CPI – well known for their long term affection for the ‘national bourgeoisie’ despite the national bourgeouisie’s long term indifference/indulgence towards them), Kanhaiya is a genuine populist nationalist and a democrat moulded as he says, equally by Bhagat Singh and Dr. Ambedkar. There is a lot to admire in that vision, even in partial disagreement. And while some may not necessarily share his nationalism, this does not mean that one has to treat it with contempt either. I certainly don’t.

Stolen Azadi or Found Azadi?

On the other hand, several, especially those in the ‘freedom’ camp in Kashmir, saw Kanhaiya’s voicing of the Azadi refrain as yet another instance of how the Indian liberal-left will ultimately sell them out, and even steal ‘their’ slogan (because, who can deny the electric charge which the ‘hum kya chantey, Azadi’ slogan has become a part of the breath of the everyday in Kashmir). While for Kanhaiya, from a peasant family in Bihar, it is perfectly reasonable to say that Azadi ‘in’ India, is not Azadi ‘from’ India, it is equally reasonable for a son of a peasant in Kashmir to say that Azadi ‘in’ Kashmir, is Azadi ‘from’ India. What else can you say when you are stared down by an Indian tank?

But the best response that I found to the ‘resentment/ressentiment’ of the Kashmiri Nationalist Copyright Holders on the Azadi slogan has come from another Azadi-Parast young Kashmiri – Arif Ayaz Parrey – so I will simply listen to him, and I urge you all to do the same. This is a status update on his Facebook wall:

[su_quote]I would like to offer my humble disagreement with some fellow Kashmiris who think Kanhaiya misappropriated the slogans of azadi from Kashmiris during his speech at JNU yesterday. First of all, azadi kisse kay baap ki jaagir nahi, it does not belong to an individual or a group. It belongs neither to India nor to Kashmir. It is an aspiration every living being possesses, and that is that. Two, if Kashmiris think they have a copyright (geographical indication, for the legal-anals) over the slogans of azadi, they should not use the Urdu language, which is spoken in many parts of India and Pakistan as well. They should invent slogans in Kashmiri, Sheena, Dogri, Balti, Pahari, Gojri etc. Three, Kanhaiya is not a Kashmiri, he is a Bihari and right now and historically there has been no demand for azadi from India in Bihar. So of course he does not want azadi from India. Why is that surprising? By asserting that “we want azadi in India, not from India” he is distinguishing himself from Kashmiris, excluding them from the “we” and thus setting them free to pursue their own agenda: The agenda of azadi from India. Why is that a problem? Both Kanhaiya (as a representative of a certain strand of left-liberal thought in India) and Kashmris are seeking “freedom from”, in our case we have a crucial additional term in “freedom from India”. This pursuit of negative liberty should not be equated with positive liberty spilling into fascism, aka RSS, aka “Arbeit macht frei”, though that is coming soon enough and will try to sweep away both us (struggling against it) and the Kanhaiyas of India (trying to snuggle under its arm).[/su_quote]

I am interested in what happens when Arif Parrey and Kanhaiya Kumar find it possible to listen to one another.

In his interview to Ravish Kumar, Kanhaiya spoke about a ‘programme of minimum unity’ that could bring together all those united by their revulsion of the RSS agenda. One picture of a such a coalition is clear – it brings together the mainstream parliamentary left, the Congress, the Non-Congress regional forces, sections of the non-parliamentary left, some ultra left groups and civil society organizations. This is a picture of a coalition that could easily unseat the BJP regime in India. And in all likelihood, this picture will take shape in the near future. It is taking shape because the BJP regime, with its incompetence, its violence and its stupidity is actually helping it take shape.

This would the ‘Azadi in India’ camp. But for reasons I would like to argue for a little later, I think that mere ‘Azadi from the BJP-RSS’ alone will not add up to ‘Azadi in India’. For that to happen, the ‘Azadi in India’ may have to imagine an even broader alliance – including with some of those who are currently in the ‘Azadi from India’ camp. We can leave the prepositions for a grammar lesson, but right now, if we are to build a new vocabulary of politics, we might as well ask for a strategic blurring of the distinctions between in, from, for, and to – and simply stay with the noun – Azadi. Lets find a strategy of maximal solidarity, even within the framework of a tactics of minimal unity.

The current situation in JNU makes this possible in a refreshingly pragmatic sort of way. Everyone knows that between Kanhaiya, and his friends – Umar, Anirban, Asutosh, Rama Naga, and Ananth, and Shehla, within and between different organizations and tendencies within the broadly democratic Left and Dalit groups, (drawing on different Marxisms and Ambedkarite traditions) on campus (AISA, BAPSA, ex-DSU, DSF, AISF and other independent formations), there are many differences about what ‘in’ and ‘from’ mean – but there is a broad, working understanding of what ‘Azadi’ itself is all about. And here the broad contours of an open ended, anti-caste, class and gender sensitive, democratic socialism is what seems to be on offer. This is what was expressed with great depth and clarity by Kanhaiya Kumar, with nods in the direction of Bhagat Singh, Ambedkar and Marx, in his ‘ghar-wapsi’ speech. This is what the new slogan ‘Neel Aasman pe Lal Sitara, Yehi to Hai Pehchan Hamara’ (the synthesis of the ‘Blue’ Ambedkarite traditions with the ‘Red’ Left traditions to form a completely new political reality) means in practical terms.

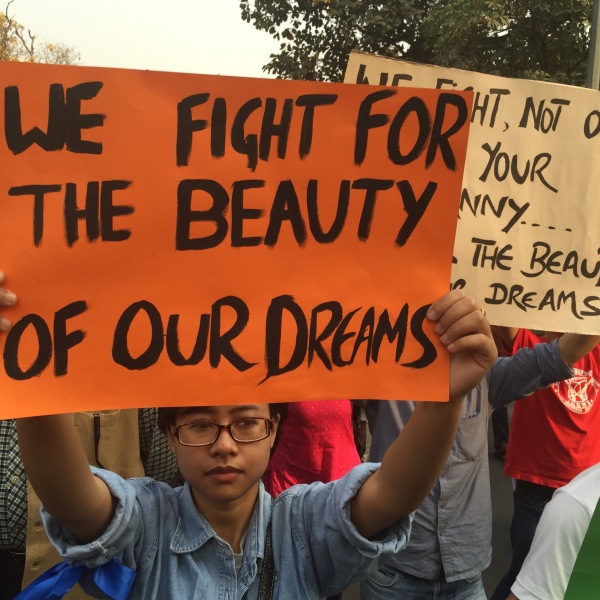

This is a proposition grounded in real solidarity, in friendship and comradeship that should set an example for the entire broad left-democratic milieu in our times. It was typified for me by the JNU Vice President Shehla Rashid’s call for the March on Parliament on March 2nd, to come with ‘any colored flags’ – which led to a polychrome coalition of Red, Blue, Tricolor, Black and Rainbow shades – and even the presence of a brave young ex-ABVP activist amidst them who could not but confess to his own inner turmoil and transformation. Even Bhagwa, or shall we call it Basanti, is a beautiful colour when snatched out of the hands of fascists (We can leave the dull Khaki to them to cover their shame.)

A Polychromatic Spectrum of Friendship and Dissensus

These young people, emblazoned with different colors, with different hues and shades, argue with each other passionately, and then sing songs together, laugh, hold hands and embrace each other. They stand by and for each other despite their serious differences. I find this solidarity in dissensus (which increasingly disregards the sectarian anxieties of some, thankfully not all, of their teachers, leaders and mentors) one of the most beautiful things to have come out of this spring in JNU.

Kanhaiya Kumar, Rama Naga & Shehla Rashid, with other students, on the night of Kanhaiya Kumar’s release on Bail (Photograph by Sumanta Roy, JNU)

I hope that between themselves, Kanhaiya, Umar, Anirban, Shehla, Ashutosh, Rama Naga Chintu Kumari and Ananth, and all their friends and comrades maintain and nurture this solidarity, this sense of ‘one for all and all for for one’, this unity of red (Left) and blue (Dalit), which has eluded their ‘mature, adult’ leaders till now, and which has so far made it impossible, despite many concerted attempts, to break student unity in action. Between themselves, and their origins, they encompass a huge spectrum, Dalit, Kashmiri, Adivasi, Urban, Rural, Working Class, Peasant, Intelligentsia. Their political positions occupy many locations around a wide spectrum. Some are sympathetic to Kashmiri self determination, others see a vision of an India of federated peoples, others prioritize the annihilation of caste, still others are trying to evolve a gendered critique of Maoism from positions of proximity. They agree on a lot and disagree on a lot.They have parents who are farmers and teachers, brothers who are soldiers, mothers who are nurses and sisters who are the future.

A slogan that I have seen in the protests occasionally is – ‘The Life of the Mind Shrinks with Consensus, Expands with Dissent’ – I think the original quotation (is it from Ranciere?) uses Dissensus, rather than Dissent, but the point being made is unmistakable.

Consensus, even around the question of what nationalism is, or what freedom can be, kills the life of the mind. Or as Umar Khalid put it so well, only recently.

In fact I find this openness, which has worked on the ground in JNU very well since the 9th of February, a much more attractive and pragmatic possibility than the prospect of the sudden narrowing down of what ‘Azadi’ might come to mean if the finer points of the distinction between ‘in’ and ‘from’ (egged on by media mavens and ‘well wishers’ who want youthful idealism and at the same time want a nice, cosy, telegenic form of Azadi) override the unity that transcends the grammar of older slogans exactly as the . In the name of the claiming of a programme of ‘national unity’ by the parliamentary left, there is the real danger of losing the practical, day to day, unity of action that has brought a lot of students together, transcending sectarian considerations, in the last few days. I hope that the ‘parliamentary left’ and their friends in Lutyens Delhi can see the wisdom of staying away from the temptation of making a mess in the name of ‘national unity’. It will actually be in their best interests.

The Politics Beyond This Moment

I want us to think together about what it might mean to build on that – practical, on the ground sense of solidarity , and i want to try and think about whether or not it can actually serve as a possible model for an alternative politics, beyond JNU, beyond campuses, beyond states and borders.

For the sake of an argument, let us call this (and with all due respect to Kanhayia’s tentative formulation) another possibility of minimum programmatic unity of three kinds of ‘azadi-parasts’ – the solidarity of those who want Azadi ‘in’ india and of those who want Azadi ‘from’ India and even of those who simply want ‘Azadi’ regardless of ins, froms or any other kind of prepositional qualifications.

This is a vision of Azadi that in my view be the basis of a conversation that pays equal attention to the desire for freedom, justice, dignity and peace amongst students, amongst the young, amongst Dalits, amongst and with women and girls of all ages, amongst workers and those who till the land, amongst those who dwell in forests, mountains and cities, amongst those who face the brutal reality of a military occupation, amongst a whole new class of political prisoners, and even amongst those who are sent needlessly to soldier and brutalize others, and amongst the loved ones of those whose uniformed bodies return home in second-rate coffins from avalanches and ambushes in far away places.

Conversations Overheard at Dawn and Twilight, between Today and Tomorrow

I am talking about a vision of freedom that can be a thread of conversation between the JNU student, the Honda worker, the Maruti worker in Prison, the young Dalit student whose body and soul are sick of humiliation and patronizing innuendoes, the farmer contemplating suicide, the young woman on the street, asking to be left alone to enjoy herself, the Kashmiri teenager who is angry enough to risk everything and pick up a stone, the Manipuri mother who strips naked in front of an Indian army base, the Jawan sent to fight wars and insurgencies that mean nothing to him (and who simply, like the rest of us, wants to stay alive), the Adivasi in the forest or at the edge of a strip-mine, the migrant African citizen of the world who lives in Khirki village battling landlords and racist busybodies, the queer woman who has trouble with her parents, the sex-worker at work and the young Muslim man or woman who has nightmares of being encountered. Each one of these bodies, these lives, these stories, wants Azadi and wants it now.

I am deliberately presenting a very wide cast of characters, because I believe that if ‘Azadi’ has to mean anything at all for even one of these different kinds of people, it cannot do so at the expense of what it might mean for any of the others. For some of these people ‘Azadi in…’ makes sense, for some ‘Azadi from…’ makes sense, for others ‘Azadi for…’ makes sense, for yet others, ‘Azadi to…’ makes sense. They all make sense to me.

Some years ago, in the wave of spontaneous protests that erupted all over Delhi in the wake of the brutal rape and murder of Jyoti Singh in 2012 I was surprised into a recognition of the way in which the sound of the word ‘Azadi’ resonated in the streets of Delhi.

This is what I wrote then, on New Years Eve, 2012. Reading these words now, I recognize the gleam of prophecies hidden within them that i had not known then. I know them now. They are no longer prophecies, they have turned into radiant desires.

Flashback to a Post Written on the night of December 31, 2012

“…I am not writing to tell you what I think today. I am writing to you because I am a chronicler of your desires. A witness to your witnessing. I am writing to you because I listened to you, because I want everyone to hear what you said to me, to anyone who cared to listen, to the city and be world. And so, I will simply reproduce below what I heard. I will retrieve from my memory of this ordinary and extraordinary evening fragments of slogans, snatches of conversation and song.

There was of course the ubiquitous refrain of the question that was also an answer – Hum Kya Chahtey, Azaadi. Which you would then immediately respond to by saying, to yourselves and the world – the following :

Raat mein bhi Azaadi. Din mein bhi Azaadi.

Daftar mein bhi Azaadi. College mein bhi Azaadi.

Hostel mein bhi Azaadi. Schoolon mein bhi Azaadi.

Karkhanon mein bhi Azaadi. Khalihanon mein bhi Azaadi.

Sadak pe bhi Azaadi. Gharon mein bhi Azaadi.

Shadi karne ki Azaadi aur Na Karne ki Azaadi.

Pyaar ki bhi Azaadi aur Dosti ki Azaadi.

Behan mangey Azaadi. Bitiya mangey Azaadi. Ma bhi mangey Azaadi.

Mang rahi hai Aadhi Aabadi. Azaadi. Azaadi.

Kashmir mein bhi Azaadi. Manipur mein bhi Azaadi.

Chhattisgarh mein Azaadi aur Dilli mein bhi Azaadi.

Jangal mein bhi Azaadi. Shahron mein bhi Azaadi.

Gaon mein bhi Azaadi aur Kasbon mein bhi Azaadi.

Punjivad se Azaadi. Manuvad se Azaadi.

Mohalley mein bhi Azaadi. Pure desh mein Azaadi aur Duniya mein bhi Azaadi.

Bap se bhi Azaadi aur Khap se bhi Azaadi.

Dharam se bhi Azaadi aur Sanskriti se bhi Azaadi.

Samaj se bhi Azaadi. Sarkar se bhi Azaadi.

Kapre pehen ne ki Azaadi. Kuch bhi pehen ne ki Azaadi.

Denting-Painting ki Azaadi. Pub mein bhi Azaadi.

Bus-Metro mein Azaadi aur Disco mein bhi Azaadi.

Mandir mein bhi Azaadi aur Masjid mein bhi Azaadi.You embraced the Azaadi slogan, took it from where it came, turned it, played with it, made it dance and now you return it, enriched and enlarged. Now, when your peers chant it in Kashmir, they will echo you, just as you have echoed them, even as you both speak of and to different and similar kinds of desires for freedom. Different and similar sources of pain. This is how, with echoes and resonances, with rhymes and reasons, new solidarities are born and nurtured.

[ Where does a slogan come from ? The Azaadi chant, spoken the way it is in the streets of Delhi today, like the Mahabharata, has more than one beginning, more than one end. To many, in their late teens and early twenties in Delhi. It comes from what they have first heard, in this our time, now, echoing from beyond the mountains in Kashmir. They have heard it in demonstrations by Kashmiri young people in Delhi. They have heard it on television, they have felt its immediate and visceral power in Sanjay Kak’s film – Jashn-e-Azaadi, which several of them have fought to screen in their colleges. But it also has another provenance, another set of matrilineages. Nivedita Menon has reminded me that it came via Pakistani feminist groups, via a song and set of chants rendered by Kamla Bhasin in an earlier moment of the feminist movement in Delhi. A slogan and a political moment inherits and is a carrier of different bits of DNA, different sets of political nuances and desires. None is more important than the other. Though in terms of provenance, some may have greater priority. Here in priority, I stress the meaning of ‘prior’ as in before. And even ‘priority’ in this sense can mean different things, for different ends. It can mean when a slogan was first articulated, it can also mean when a slogan was first heard, it can also mean when a slogan was first snatched from the air, from history, from memory, and it can also mean when a slogan was first echoed. It can mean each and all of these things at the same time. The miscegenation of these different bits of DNA point to a mitochondrial Eve, a first mother, as well as to a daughter in the far future, who, like the poet Vidrohi said outside the University Metro Station as the protest paused at night, is the mother and daughter of us all. We share one present, many pasts and many futures.]

You spoke against Pitrisatta, Manuvad, Pedarshahi, Patriarchy (and now, in 2016, I have heard you speak against Punjivad – the big daddy – Capitalism itself)

You spoke against female foeticide, sexual harassment in the work place, about the exploitation of women workers, about violence within the home, within marriage.

You said the obvious and still the necessary thing to say – Nari Mukti, Sabki Mukti.

You said Hallabol to the State, the Army, the Police, UPA and NDA.

You said Hallabol to Sonia Gandhi, Sheila Dikshit and Sushma Swaraj.

You said Jo Na Boley, Us Pe Bol, Hallabol, Hallabol.

You spoke against the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act.

I saw a hand written sign remembering Nilofar and Aasiya Jaan.

I saw hand written signs against marital rape and custodial violence.

I even saw a hand written sign against how publishing companies have locked up the photocopiers on campus.

I heard the names of Bhagat Singh and Rosa Luxemburg hurled into the air in one strange keening cry. I heard another voice say ‘Kaun, Who’ and I heard another voice say ‘Abey, Rosa, Rosa’ as if you were talking about a classmate. And then, it was – ‘Inquilabo, Inquilabo, Inquilabo Zindabad’ again.

Then you talked about Hostel Deadlines. 8 Pm Curfews. About library hours.

You talked about hostel accommodation and transport and why there are so few women’s toilets.

I heard the words of a beautiful song, the sharpest song that I have ever heard about the sanctum sanctorum of Lutyens’ Delhi, where they think they can decide your fate. A fragment of the song went something like this.

Chaurasi banglein hai Rama, banglon mein bageechey

Behisaab marghat hai inki har kyaari ke neeche

Tod na lena inke naazuk nakhrey vaaley phool ko

Khadi hui hai police-military talwaaron ko kheenchey

Saheb ke daftar ke bahar khadi hui hai zindagi

Fir raddi ke tokr mein padi hui hai zindagi

Paise ke hathode se shoshan ne iski maar ki

Ki jagah-jagah se tukda-tukda toot gai hai zindagi

Chaurasi banglein hai Rama, banglon mein bageechey

Behisaab marghat hai inki har kyaari ke neeche …[ Thanks to Anmol Ratan from AISA, Delhi University, for sending me the lyrics of what was sung yesterday ]

(Eighty-four bungalows for each of them, and for every bungalow a lawn;

piles of laundered cash for them to make their beds upon.

Don’t touch these dainty flowers of theirs that sigh and faint away:

cops and soldiers guard their gates with naked swords drawn.

At the Big Man’s office door my life stands waiting with a file;

once more I find my life cast out upon the garbage pile.

My life is broken everywhere: their clubs of solid gold

have gone about their business in the old accustomed style.)

{Thanks, Sandeep Srikumar for help with the translation of the ‘Chaurasi Bangla’ song? }

I heard voices getting tired. I heard one voice pick up the thread of a slogan where another trailed. I heard one cluster of voices answer another cluster of voices…”

A Brief Etymologica Digression

Let’s time travel back from that night in 2012 to this night in 2016 and then time travel back to the time of the origin of words. So what does ‘Azadi’ actually mean, where does it come from? Where can it take us?

azadî

From Middle Persian ʾcʾt’ (āzād, “noble; free”), from Old Persian (āzāta-), from Proto-Iranian *āzāta-. Cognate with Avestan (āzāta-, “noble”), Manichaean Middle Persian ʾʾzʾd (āzād), and Parthian (āzāt, “noble”). Akin to Old Armenian ազատ (azat), Georgian აზატი (azaṭi), Iranian borrowings. Sometimes used to describe a class of lesser nobility – ie – people of free birth who were neither high aristocrats, nor slaves or serfs. Cognate with the Greek Ελεύθεροι (Elutheroi)

Ultimately from the past participle of Proto-Iranian *zan- (“to be born”), from Proto-Indo-European *ǵenh₁-, originally meaning “born (into the clan)” and, by extension, “noble” and “free”.

See the entry for āzād” in David Neil MacKenzie (1986), A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary, London: Oxford University Press and in Iranica Online.

So it is a really old word, suggesting a kind of person – free born, and a kind of situation – of freedom, that has been a part of the cultural, ethical and political dna of many different kinds of populations in our part of the world. People were singing songs about Azadi before nation states or empires, and my guess is that they will sing songs about Azadi a long time after the passing of nation states and empires. The word was carried by wandering tribes of the past, and it will be carried by the wandering bands of the future. It is the greatest infection that the human race has seen, one that has inoculated us and given rise to antibodies crucial to our health and well being. It is what keeps us immune to disasters, in love and alive.

What interests me most in the word is its etymological link to the fact of being born, of coming into life. Even the word Nation, in English, in German, and in Romance Languages like Italian and French has a connection to birth, to nativity, and hence to the idea of nativity. But while nation, natio, native – locates and identifies a birth in a place, a tie, a bond (often expressed in earlier societies by burying an umbilical cord in the earth where one is born). Azad, on the other hand has a sense of being born to move, to be free. Nation predestines one to be someone from a place, Azadi asks us about where we are going to, about who we want to be. If Nation ties us to a ground, to a past, then Azadi takes us forward, into the world, into the future.

Azadi In, Azadi From, Azadi For – Three Ways of Dancing to the Music of Freedom

While agreeing absolutely with Kanhaiya Kumar that millions of people want ‘Azadi in India’, it is also important for us not to forget that millions of other people may also want ‘Azadi from India’. Both are expressions about the future, both are breathed into life by desire. I want us to entertain the thought that these two desires could be in conversation with each other.

And that ‘Azadi in India’ might require that we listen to those who want ‘Azadi from India’. That these two propositions about and for the future might even have something in common. How could that be?

The only way that people in this land will be free, abad, of want, hunger, indignity is through peace in South Asia, and that can happen only when the people who do not want to live under a military occupation in say, Indian administered Kashmir, or a Pakistan administered Baluchistan, are free to choose their own destinies in peace. It is Azadi in the far flung insurgent territories of India and Pakistan that can finally give peace to the Indian and the Pakistani soldier. If we really care for the Indian and the Pakistani soldier then we must demand that they no longer be sent to Kashmir or to Baluchistan to return in coffins.

It is only then that the absurdity of India and Pakistan locked in a constant hostile nuclear war dance can come to an end. It is only then that we can get rid of pointless standing armies and concentrate on the social needs of all the peoples of the subcontinent. ‘Azadi in India’ and ‘Azadi in Kashmir and Manipur’ , or ‘Azadi in Baluchistan (from Pakistan) for instance, need not be seen as mutually contradictory slogans. In fact, the voicing of each slogan might require the understanding of the other. And then we can get down to the real business at hand, the dismantling of states and borders and the formation of a world community of free and associated producers. That, is the real meaning of Azadi, everywhere.

Azadi from the festering sore of a militarized occupation by India in Kashmir may be finally crucial fur us to arrive at Azadi in India from violence and want. This is where the different visions of ‘Azadi in India’ and “Azadi from India’ can meet and look each other in the eye. This is what makes it necessary for us to hold both Kanhaiya and Umar’s hands. Unconsciously, despite whatever the court order says, we all know this. Kanhaiya knew this when he went to defend Umar and his comrades from the ABVP assault on the 9th of February. This is what makes us, who are friends of Kanhaiya, Umar, Anirban, Ashutosh, Rama, Ananth, Shehla, Aparajita and Aishwarya, insist that we won’t fall into the trap of supporting one student and condemning another. We won’t fall into the trap of asking for war (koi bhi jang nahin, kabhi bhi nahin, kahin bhi nahin), for destruction (barbadi), neither in the name of India, nor in the name of Pakistan, not even in the name of Kashmir. We, who have nothing to lose but our chains and only a world to win have no need to pray for the breaking of lands into thousands of fragments (hazaar tukde), because, fundamentally we do not believe in borders. We may be born, be native, in this or that village, des, or nation, but we are Azad to live in and claim the world. Our freedom liberates the soldier from the uniform, the worker from the factory, the student from the prison. We insist on this freedom, not later, not kabhi aur, not aisey-vaisey, not just yahan-vahan. We want it now, we want it everywhere.We who are nothing, shall be all.

Let me amend the lyrics a little, from this wonderful song from the film ‘Fir Subah Hogi’

Chin-o-Arab Hamara,

Hindostan Hamara,

Pakistan Hamara,

Yeh Kashmir bhi Hamara,

Rahne ko Ghar Nahin Hai

Sara Jahan Hamara.

We know that Rohith Vemula had written of being close to the stars in his last letter. This is what Afzal Guru had written in one of his last letters.

[su_quote]I am a citizen of this planet. I do not believe in chosen land, chosen race, concepts which are diabolical, devastating and disastrous in their consequences and results. There is only one way to come out of these policies of nationalism, that is, we must believe and practice the universal permanent values…Francis Fukuyama’s liberal democracy is not the ‘end of history’, rather the political philosophy towards the end of all human moral values. It is this neocolonialism we are prisoners of, but unaware of the prison walls in which we are caught. Our tastes, desires, and imagination are all imprisoned, this is where the greatest danger lies. My ideas may seem more utopian and larger than life, but one should never escape from individual responsibility. Every person has a special vital role to play in this world. Everyone is accountable for their personal, individual deeds. No one can share the burden of other souls. It is our sincere deeds which will go with us. Everyone comes alone and goes alone. We can develop ourselves only when we develop our concerned societies and humanity as a whole. Humanity will develop only on the basement and foundation of universal permanent values. Let the noble thoughts come from every side. In the end, I request you: don’t colorise or dress my words in any colour or dress, except a purely responsible human concern for humanity. I am in universe in such a way that I made myself the universe, I live in a space but I am spaceless. With regards and respect, Mohammad Afzal Guru, High Security Ward, C Jail number 1, Tihar.[/su_quote]

If there are ghosts, and if Rohith Vemula and Afzal Guru are ghosts now, it is possible that there may be a conversation between two happy ghosts somewhere in a constellation made up of a star and a planet visible above the horizon between Hyderabad, Telangana and Haiderpura, Kashmir. We can listen to that conversation, between Azadi ‘in’ and Azadi ‘from’, and find ways to talk in new and uncannily beautiful ways, about where we are, not just here, on earth, but in deep space and deep time. I believe that the contours of this conversation can shape and be the future. That will be a Azadi worth our dreams and our hopes.

Kanhaiya, Umar, Anirban, Rama, Ashutosh, Anant, Shehla, Aishwarya, Aparajita and the rest of them in JNU have already started talking to each other. All we need to do is to join them. Keep the conversation going, free of the noise and interruptions of TV anchors and Neta-Log. All it will take for us to do this will be some determination and a lot of hot, sweet, tea through the coming days and nights.

We might find then that the country without a post office has found a way to send a telegram to the world. We may even be able to recognize it as yet another instance of the first telegram of the last international.

I leave you with five different incarnations and incantations of Azadi. Minimum Unity, Maximum Solidarity.

First, the by now raging hit, Kanhnaiya’s voice, ringing Azadi into the Delhi night, accompanied by his dafli, perhaps during an Occupy UGC protest.

The second is the Indian feminist Kamla Bhasin’s rephrasing of the Azadi chant that she had learnt from her Pakistani friends.

The third sonic magnet is the daily breath of Kashmir – recorded in a village somewhere in the valley.

The fourth is a Kurdish Rap track (heard regularly by the brave young women and men of Kobane and Rojava who are trying a new form of polity – that is something quite out of the ordinary way of thinking about states – through their experiments with the Cantonal Constitution of The Kurdish Autonomous Territories of Rojava, Kobane, Afrin and Jazira (Remember, the self determination of the Kurds requires the passing away, or radical alteration, of the shape of four nation states – Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria – so naturally the Kurds have had to give a lot of thought to the question of going beyond the nation-state as an organizing principle for azadi)

Fifthly, is a song by the ‘seditious’ Tamil bard – Kovan – called Azadi, and dedicated to the JNU students.

Enjoy the music, hear the echoes, lets keep talking, singing, and breathing freely. Lets keep it rocking.

Jai Bhim, Joy Guru, Lal Salam. Inquliab Zindabad

————————————————————————————————-

This text is being released simultaneously on Kafila.Org and ww.raiot.in so that it can reach many different kinds of readers, and in the hope that like the students in JNU, we who run blogs and online initiatives can build on minimum unities and maximum solidarities. I am grateful to several conversations and posts on Facebook through the day that have helped me shape these thoughts. A brief excerpt, extracted while the germ of this text appeared as my Facebook status updates, was published in the Daily O.

Be First to Comment